Why are female secondary heads £6K worse off than men?

The average female secondary headteacher is paid £5,765 less than her male counterpart each year, according to new government data.

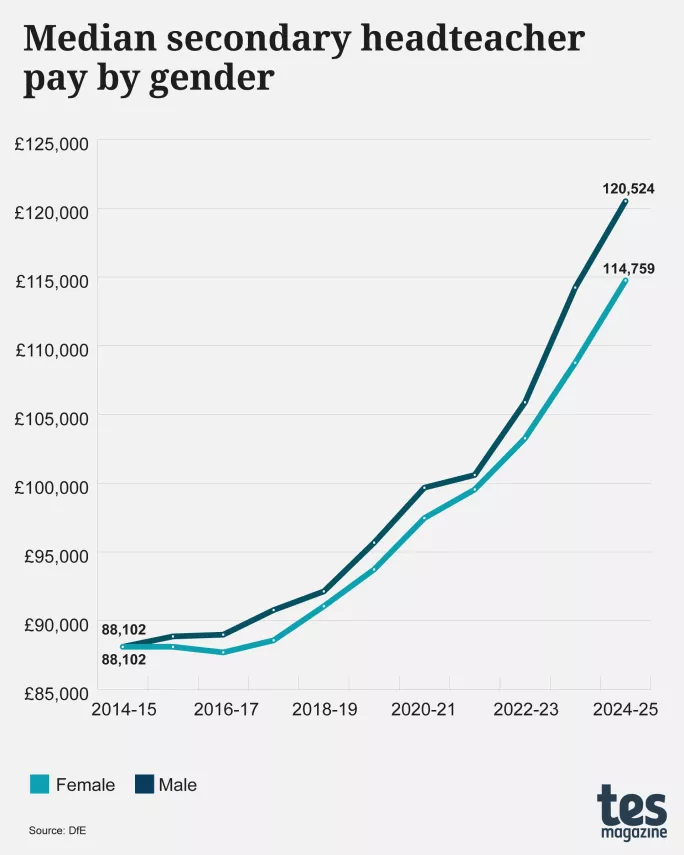

The latest school workforce report, published last week, shows that as of November 2024 the median salary for a female headteacher in a state secondary school is £114,759. For a male secondary head, it’s £120,524.

Over the course of a headship, that missing £5,765 each year certainly adds up. While there is no recent figure for the average headteacher tenure, a 2008 research study by the National College of School Leadership suggested it was six to seven years.

Based on this figure, the average female head could end up as much as £40,355 worse off than a man across the course of her headship.

Even if she remained in post for just five years, a female headteacher would be £28,825 worse off. If she stayed for 10 years, that figure would be a whopping £57,650.

While this acknowledgement of a gender pay gap isn’t new - in education or any other sector - what’s particularly interesting is that it hasn’t always been like this.

For three years from 2010, the median pay for both male and female secondary headteachers was £86,365. The male median overtook the female median in 2013, but then parity was once again reached at £88,102 in 2014.

The persistent gender pay gap

However, over the past decade there has been a persistent and growing gender pay gap for headteachers - as you can see in the graphic below.

What began as a £756 difference between male and female pay in 2015-16 has widened. This has been particularly significant in recent years: the gap more than doubled from £1,056 in 2021 to £2,618 in 2022, and then again to £5,464 in 2023.

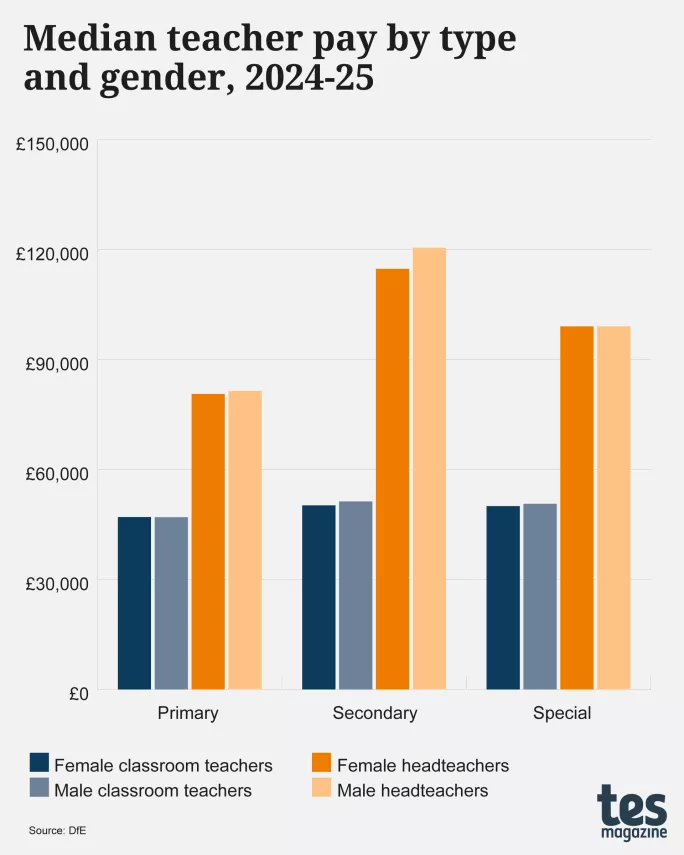

Interestingly, this gender pay gap is not replicated to the same extent in any other teacher type across the sector, as you can see in the graphic below.

There is a gender pay gap of £807 at the primary headteacher level: the median salary for women is £80,634 while for men it is £81,441. But for special headteachers, there is no gap at all: the median salary for men and women in those roles is £99,067.

There are gender pay gaps for classroom teachers: in secondary settings, a male teacher’s median salary is £1,070 more than the median for women, while in specialist settings, it’s £635 more.

But for primary classroom teachers, the trend is reversed: a female class teacher earns £33 more.

Clearly the gap at secondary headteacher level is the focal point of this problem.

‘Demoralising’

“I never fail to be disappointed [by the gender pay gap in leadership],” Keziah Featherstone, executive headteacher in the Mercian Trust and co-founder and vice-chair of WomenEd, tells Tes. “For a feminised workforce that is meant to promote equity, it is shocking.”

Indeed, women make up 64.6 per cent of the total secondary headcount, yet just 43.2 per cent of secondary headteachers. In 2024 there were 1,678 female heads and 2,204 male heads.

“It’s demoralising, knowing the person doing exactly the same job as you, perhaps even within your network, is being paid substantially more,” Featherstone adds.

The pay gap - and because £5,765 is a median, “there will be much bigger discrepancies”, Featherstone points out - leads women to “lose trust in the system”, which is a particular problem given the sector’s ongoing recruitment and retention crisis.

This view is echoed by Caroline Barlow, headteacher of Heathfield Community College and co-chair of the Headteachers’ Roundtable. “What’s the pipeline of women into senior leadership positions? Hearing those kinds of figures is just one more drip feed of discouragement to apply,” she says.

‘For a feminised workforce that is meant to promote equity, the pay gap is shocking’

What’s less clear is why this gap has emerged, considering that it hasn’t always been there.

James Zuccollo, director for school workforce at the Education Policy Institute, tells Tes that it could be because of a quasi-positive reason - more women have entered headship roles over the past 10 years. In 2014, 37.6 per cent of secondary heads were female; now it’s 43.2 per cent.

“If many of these new headteachers are less experienced [and therefore sit on the lower spine points within the headteacher pay band], it could be lowering the average salary for women overall,” he says.

However, others say one issue is that multi-academy trusts can set their own pay, which will only have more of an impact now that academies outnumber maintained schools for the first time ever.

“Trusts can pay what they want, and I don’t think that is always positive,” says Featherstone.

Having more room for negotiation means that men are more likely to negotiate higher pay, says Barlow. She explains how there is “a lot of evidence around men being more hard-nosed about negotiation than women” - including academic research showing that women typically ask for less than men.

The motherhood penalty

Barlow adds that societal norms around gendered working pattens also play a part: “More women take gaps in their career” - including to have children.

This is what Emma Sheppard, founder of the MaternityTeacher PaternityTeacher Project, calls “the motherhood penalty”, explaining that, statistically, the pay divergence for women comes in their thirties. “They’re doing OK and then they have a baby, and then everything goes wrong from there.”

Most mothers take a year of maternity leave and are more likely than men to return to work part-time - both of which affect opportunities for career progression.

Across the English state school system, almost 10 times more female teachers work part-time than male teachers: 114,160 women compared with 11,895 men. That stark difference continues at headteacher level, where 1,239 female headteachers work part-time compared with 274 men.

The pay gap data represents full-time equivalent figures, so these differing working patterns by gender shouldn’t affect pay. But in practice it does, says Sheppard, giving the example of women in a co-headship.

“If a male headteacher goes in [to a job interview] and says, ‘I want £110K for this position, and I will do it full time,’ and two women go in and say, ‘We want £110K pro rata,’ the school will say [to the women], ‘It’s going to cost us extra to have two people doing it, so we’ll give you £95K pro rata.’”

The female co-headteachers may well agree to lower salaries because they are getting a more flexible working pattern and that is valuable to them. Nonetheless, a pay gap emerges.

As such, “flexible and part-time working is a double-edged sword”, Sheppard explains, “because if they are going to be majority taken on by women in order to manage caring responsibilities, then it’s going to be women who continue to lose out on pay”.

The role of governors

Whatever the explanation, what is evident is that the gender pay gap for secondary headteachers is “simply unacceptable”, Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the NAHT school leaders’ union, tells Tes.

“We urge the government to conduct a detailed pay equality analysis for gender, and all protected characteristics, to begin to try and make progress on tackling this issue.”

‘Flexible and part-time working is a double-edged sword’

But not everyone believes it is the government that should answer for this.

Pepe Di’Iasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, describes the gap as “very worrying”, adding that the union “would urge employers to redouble their efforts to look critically at their headteacher salaries and recruitment practices [to] ensure that female headteachers are being treated fairly”.

Featherstone also believes change can be effected within the sector - particularly “at governance level, because it’s the governors and the trustees that appoint headteachers”.

“Unless governors and trustees are fully committed both to their approach of gender, race and disability equity, and undergoing substantial and conscious bias training and making sure they are rewarding colleagues appropriately, nothing’s going to be sorted out,” she says.

A sector-led solution

Fiona Fearon, head of policy and research at the National Governance Association (NGA), agrees, telling Tes that the emergence of the gender pay gap is “a governance issue” that “should prompt serious reflection - and action”.

“Governing boards must ensure that pay decisions are transparent, robustly justified and rooted in equitable practice,” Fearon says, adding that the “NGA has set out clear, practical steps boards can take, from interrogating leadership pipelines to routinely analysing pay and progression data”.

Barlow agrees that “within the sector, there is a lot that we can do ourselves”.

“We all need to play our part. We have a job to talent-spot and to nurture and develop women leaders as much as men.

“The more we can share experiences, the more equipped women will be to not feel like they’re on their own in any negotiation room.”

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article